Visa Digital Calendar

The digital calendar is the main program for which we developed the visa assembly language and microprocessor in the first place. It was part of the original class assignment that sparked the beginning of the bopkit project.

The goal was to write an assembly program to drive the display of a digital calendar that showed the date and the time of day.

7-segment display

The 7-segment calendar display is an OCaml Graphics application. It is implemented here.

It is available in the command line as:

$ visa digital-calendar display

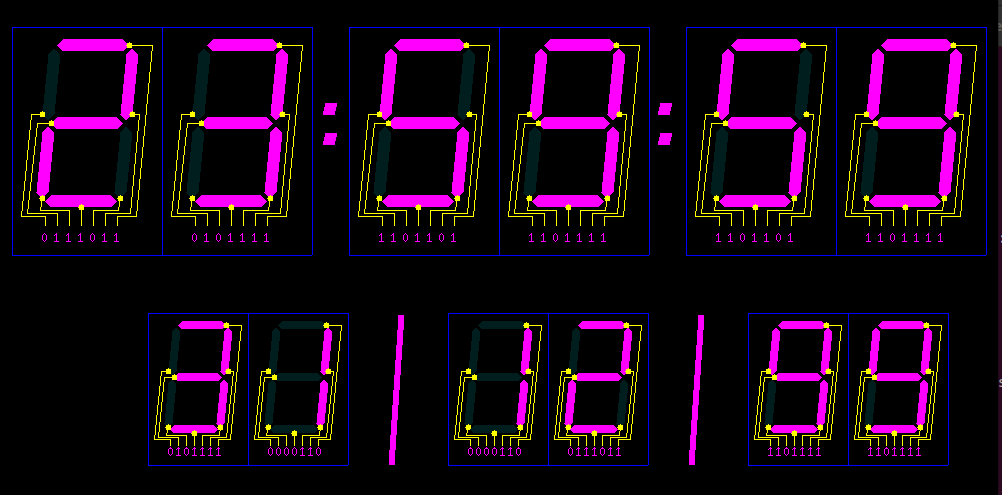

This opens up a OCaml Graphics window, and displays a 7-segment calendar that looks like this:

The application expects 91 bits on stdin, and responds by a blank line on stdout (this is the protocol for an external bopkit app of that interface).

You may try to feed a few inputs to play around with it. It's possible to use 7-segment to display some letters too!

$ visa digital-calendar display

0000000101111110110001011000111100111101100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 <-- to enter on stdin

Testing the display

In order to test the display we added a command called gen-input that will

generate valid inputs based on the current date and time of day. You may simply

connect the two applications together using a unix pipe:

$ visa digital-calendar gen-input | visa digital-calendar display --no-output

Using a textual format

So we can check in the output of calendar simulations into textual regression tests, we added a command that consumes the same input as the graphic calendar and output the date and time in a textual format.

$ visa digital-calendar gen-input | visa digital-calendar print

22/04/23 - 15:34:06

...

Microprocessor output vs Calendar input

The microprocessor visa uses an output device to communicate with the outside world. In order to drive the digital calendar, we'll make use of 6 bytes of the output device, each encoding a value on 8 bits (between 0-255) for each of the digits of the time of day (sec, min, hour) and the date (day, month, year).

However, these bytes cannot be directly connected to the calendar display, because its input is not directly compatible. Indeed, the display expects 7-segment codes.

During the hardware simulation, as you'll see we'll use a small circuit that makes the connection between the two components (the microprocessor and the calendar display) and maps the output of the microprocessor into an input directly consumable by the display.

In the meantime, we want to be able to test the same operation implemented fully

in the software world. So we've added two more commands, gen-raw-input and

map-raw-input. The first one simulates what the microprocessor will output,

while the second simulate what the translating circuit will have to do.

To exercise this all, run:

$ visa digital-calendar gen-raw-input \

> | visa digital-calendar map-raw-input \

> | visa digital-calendar display --no-output

Assembly program

We're now ready to implement an visa-assembly program to drive the digital-calendar!

We're using internal memory addresses for each of the sec, min, hour, day,

month, and year, which we named using the define construct. We have part of

the code responsible for computing the expected number of days on a given month,

and make sure to call that code whenever we're beginning a new month. The code

starts by computing the expected number of days in February, and this code is

executed again each time the year changes.

The digital calendar program implemented in visa-assembly.

// A visa-assembly program to drive the display of a digital-calendar. This

// program was originally implemented by Mathieu Barbin & Ocan Sankur in 2007.

// GLOBAL VARIABLE DECLARATIONS (ADDRESSES).

define february 7

define year 5

define month 4

define day 3

define hour 2

define min 1

define sec 0

define days_in_current_month 8

// For a constant [x], [minus x] stores [-x] into [R1].

macro minus x

load $x, R0

not R0

load #1, R1

add

end

// Increment [var] by 1. If it equals [modulo] goto [carry_label],

// otherwise goto [return_label].

macro increment var, modulo, return_label, carry_label

load $var, R0

load #1, R1

add

store R1, $var

load $modulo, R0

cmp

jmn $carry_label

jmp $return_label

end

macro write_to_device_out local_address, device_address

load $local_address, R0

write R0, $device_address

end

// Computing the number of days in february:

COMPUTE_FEBRUARY:

load year, R0

load #3, R1

and

// If it is divisible by 4

jmz @29

jmn @28

29:

load #29, R0

jmp @FEB_WRITE

28:

load #28, R0

FEB_WRITE:

store R0, february

// MAIN PROGRAM

UPDATE_SEC:

sleep

write_to_device_out sec, 0

write_to_device_out min, 1

write_to_device_out hour, 2

write_to_device_out day, 4

write_to_device_out month, 5

write_to_device_out year, 6

// COUNT_SEC

increment sec, #60, @UPDATE_SEC, @COUNT_MIN

COUNT_MIN:

load #0, R0

store R0, sec

increment min, #60, @UPDATE_SEC, @COUNT_HOUR

COUNT_HOUR:

load #0, R0

store R0, min

increment hour, #24, @UPDATE_SEC, @COUNT_DAY

COUNT_DAY:

load #0, R0

store R0, hour

// Calculate days_in_current_month

load month, R0

// Is it February?

load #1, R1

cmp

jmn @FEBRUARY

// Else: (month <= 6) ==> (even month <=> 31)

// and : (month > 6) ==> (even month <=> 30)

minus #6

load month, R0

add

// If it's zero, then month == 6

jmz @LE6

// Otherwise we check bit 2^7. If it's 1, this means the result was negative,

// thus month < 6

load #128, R0

and

cmp

jmn @LE6

jmp @G6

DONE:

increment day, days_in_current_month, @UPDATE_SEC, @COUNT_MONTH

COUNT_MONTH:

load #0, R0

store R0, day

increment month, #12, @UPDATE_SEC, @COUNT_YEAR

COUNT_YEAR:

load #0, R0

store R0, month

increment year, #100, @COMPUTE_FEBRUARY, @NEW_CENTURY

NEW_CENTURY:

load #0, R0

store R0, year

jmp @UPDATE_SEC

// Functions (with Labels) to compute the number of days in the current month:

FEBRUARY:

load february, R0

store R0, days_in_current_month

jmp @DONE

// Case if month > 6.

G6:

load month, R0

load #1, R1

and

jmz @F30

F31:

load #31, R0

jmp @W

F30:

load #30, R0

W:

store R0, days_in_current_month

jmp @DONE

// Case if month <= 6.

LE6:

load month, R0

load #1, R1

and

jmn @F30

jmp @F31

Assembled

For the program to be able to fit into the microprocessor ROM code, it has to have a binary representation that fits on 256 bytes.

$ visa assemble calendar.asm | wc -l

210

We're in good shape here!

Simulation

Now that we have the assembly program, we can simulate its execution with the

visa simulator. Whether we're running the simulator, or executing the

microprocessor on the executable won't change that the output will be the raw

output device one. To connect that output to a calendar display, we'll need to

map it. For now, we're still doing that with our software version

map-raw-input.

$ visa run circuit/calendar.asm \

| visa digital-calendar map-raw-input \

| visa digital-calendar print --clear-on-reprint

00/01/00 - 00:00:00

00/01/00 - 00:00:00

00/01/00 - 00:00:00

00/01/00 - 00:00:04

Initializing a different date

The microprocessor memory can be initialized with values, in which case the

calendar will start incrementing from that date rather than from

00/01/00 -00:00:00. We made sure this would work, so we were careful not to erase the

initial memory contents in the executable.

We implemented a small executable whose job is to create the initial memory in

the format that's expected by the calendar.asm program. That's what

get_date.exe is about. Here is an example of usage:

$ ./get_date.exe '23:59:58' '2023/01/30'

// Initial memory contents for Visa

// Generated by: ./get_date.exe '23:59:58' '2023/01/30'

01011100 // sec

11011100 // min

11101000 // hou

10111000 // day

00000000 // mon

11101000 // yea

To be able to feed this contents to the simulation, we simply save it to a file, and supply the filename to the simulator:

$ ./get_date.exe '23:59:58' '2023/01/30' > my-initial-memory.txt

$ visa run calendar.asm \

> --sleep false \

> --stop-after-n-outputs 20 \

> --initial-memory my-initial-memory.txt \

> | visa digital-calendar map-raw-input \

> | visa digital-calendar print

01/01/00 - 00:00:58

01/01/00 - 00:59:58

01/01/00 - 23:59:58

30/01/00 - 23:59:58

30/01/23 - 23:59:58

30/01/23 - 23:59:59

30/01/23 - 23:59:00

30/01/23 - 23:00:00

30/01/23 - 00:00:00

31/01/23 - 00:00:00

31/01/23 - 00:00:01

31/01/23 - 00:00:02

31/01/23 - 00:00:03

31/01/23 - 00:00:04

31/01/23 - 00:00:05

31/01/23 - 00:00:06

31/01/23 - 00:00:07

31/01/23 - 00:00:08

31/01/23 - 00:00:09

31/01/23 - 00:00:10

We'll dive into this kind of simulation and the output that this produces in more details in the section dedicated to testing visa.

Debugging

As we've seen in the Assembler section of the doc, the visa project comes with a debugger, so we've used that to feel more confident making changes to the file!

$ visa-debugger bogue calendar.asm

The whole program can be tested quite easily by tweaking the contents of the

register R1 right before it is checked to determine if the increment operation

reached the maximum value allowed for each of the sec, min, hour, etc.